Photo Essay #2

(An exploration of WWII uniforms through the examination of original period photos)

Early Printed Camouflage Uniforms of the Pacific War (1942-1943)

New Tactics & Equipment for a New BattlefieldIn the early stages of WWII Imperial Japanese ground forces demonstrated an uncanny mastery of dense jungle terrain during their breathtaking conquests of the Philippines, Dutch East Indies, Singapore, Hong Kong, Burma, and French Indochina. Defeats in these early battles left Allied leaders stunned as highly mobile Japanese combat troops, utilizing light, specialized equipment, were able to transverse what was thought to be impenetrable jungle terrain. Also, Japanese troops and snipers were often able to surprise and frustrate their opponents using effective and well-conceived individual camouflage techniques that allowed them to melt into the jungle landscape becoming nearly invisible. Combat reports from the Far East as well as costly defeats in Guam, the Philippines, and Wake Island gave US commanders a good understanding of the tactics and equipage employed by Japanese troops on the Pacific battlefields. In the aftermath of these defeats, it was clear US forces needed to upgrade tactics, equipment, and uniforms to effectively deal with a formidable enemy as well as the varied and trying environment found in the vast expanse of the Pacific. By early 1942, Japanese forces were directly threatening Australia and becoming well entrenched in New Guinea and the Solomon Island chain ‐ areas that contained some of the densest jungle and most challenging terrain found anywhere in the world. To operate on these battlefields, US forces needed uniforms that could provide combat utility and protection in an environment that included oppressive heat, constant moisture, numerous disease-carrying insects, poisonous animals, and thick vegetation. Herringbone Twill Fabric Adopted for Jungle UseAt the outset of hostilities in the Pacific, the US had no specialized tropical combat uniform available for its ground forces. In hot climates, Army troops wore a khaki service uniform consisting of a long‐sleeve shirt with stand‐up collar and matching trousers or breeches, all of which were made in 8.2‐ounce cotton twill. The Marine Corps issue was a similar affair but with the shirt being made in broadcloth and both shirt and trousers being somewhat lighter in weight than the Army type. Though these were suitable hot weather service uniforms for wear in rear areas, they were inadequate for combat in brutal tropical conditions. In the early battles of the Pacific, the cotton khaki summer uniforms proved to lack combat utility in the form of adequate pocket capacity, durability, and camouflage properties.

In early 1941 both the Army and Marine Corps adopted new work uniforms that would end up playing a crucial role in the upcoming battles of the Pacific War. Replacing traditional blue denim chore wares, the new uniforms were made in green cotton herringbone twill material and were produced in both one and two-piece designs. With the dire situation in the Pacific and no time or immediate resources available to develop uniforms specifically for tropical combat use, herringbone twill work uniforms were pressed into service to fill this role. Thus, in the summer of 1942, out of necessity, the herringbone twill work uniform became the principal combat uniform worn by US forces in the early counter-offensives in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands.

Herringbone twill work uniforms had several recognizable advantages over the khaki cotton service uniforms they replaced. The HBT uniform better facilitated movement in the field due to its roomier cut, the 8.5‐ounce HBT material was somewhat more durable than the 8.2‐ounce cotton twill, and the green shade of the material offered improved concealment in areas with vegetation. The Army, Navy, and Marine Corps all developed their own distinctive types of HBT uniforms, though Navy and Marine personnel were issued Army types when the need arose. HBT uniforms underwent rapid and continuous development during the war years with major changes primarily aimed at improving combat utility.

Because HBT outfits were principally developed for chore and mechanic duties, they would never provide an ideal solution for tropical combat use. Testing showed that HBT fabric provided inadequate protection against mosquitoes, was considered too hot for torrid tropical conditions, and became excessively heavy when saturated. Though there was considerable work done during the war to develop a specialized tropical combat uniform, these projects never came to fruition because such a uniform would require the use of new fabrics that could not be procured in sufficient quantity or with the necessary economy required under wartime conditions. Thus, HBT uniforms would go on to serve in multiple roles throughout the war years as a work uniform, combat uniform, and as a special and protective anti-gas uniform.

Individual Camouflage Comes to the ForefrontWhen the Army's entire uniform lineup came under review during the 1939‐41 period, the program sought to implement improvements in a number of areas. Thought was given to combat utility, the use of modern fabrics, and the important element of camouflage was taken into consideration as well. During this period a light‐green color, designated Olive‐drab Shade 2, was used in combination with wind and water repellent cotton poplin fabric and became the standard used in the manufacture of field garments. An ensuing development program resulted in the 1941 introduction of a field jacket, ski parka, and a series of parka type overcoats all featuring this new colored fabric. This was a radical departure from the past when field uniform fabrics were either brownish wool, khaki canvas duck, or done in animal hides and furs for extreme cold. The new consciousness for individual camouflage was clearly demonstrated when the new ski uniform was introduced in 1941. This outfit featured a reversible parka with a green side for forested areas and a white side for snowy areas and was also issued with a pair of white over-trousers and mittens to be worn in conjunction with the white side of the parka. By the fall of 1942, the olive‐drab shade 2 color had proved unsatisfactory. Field reports indicated that the light green color was too visible to be practical for combat garments. In late October 1942, a meeting was held between representatives of the different branches of the Army wherein the Office of the Quartermaster General proposed that a single color be identified that offered optimal camouflage properties for field use. This shade, once identified, would serve as a universal dyestuff for all fabrics used in the manufacture of field uniforms, equipage, and tentage. The Engineer Corps, whose responsibilities included establishing camouflage colors and patterns for the Army, balked at the idea maintaining such a color would be difficult to identify because of the great variety of terrain US forces would encounter in the global war. At the time, the Engineer Corps was advocating a reversible two-piece uniform with a solid color on one side and a printed camouflage pattern on the other. The camouflage side was to be produced in a variety of designs and issued according to the terrain it was to be used in. Disagreement prevailed within the Army over the single color concept and as a result no decision was reached at the time regarding this question. The Engineer Corps reversible suit was produced in quantity for extensive testing in the spring and summer of 1942. However, in the end, it would be rejected on the grounds of complexity and cost.

Army Ground Forces held a follow-up meeting in January 1943 in hopes of settling the question of an optimum color for field uniforms. This time the single color concept was endorsed by the committee and resulted in the dark‐green color Olive‐drab Shade 7 being approved for immediate use on herringbone twill uniforms as well as cotton duck and webbing equipment. All wind and water‐resistant fabrics were to follow as soon as sufficient dyestuffs became available. The new dark green shade was officially approved by the General Staff on 30 March 1943 and would remain the designated color for the Army's field uniforms through the end of WWII. The Navy also approved the new color for its N-3 herringbone twill utility uniform and later its N-4 field jacket. Contracts for the new OD Shade 7 herringbone twill Army outfits were let by the Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot beginning in April 1943. However, both new and old shade uniforms were produced side by side until the fall of 1943 when the old light‐shade fabric was finally used up.

General MacArthur Orders Jungle UniformMeanwhile, in July 1942 General Douglas MacArthur, Commander of Army forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, ordered the Quartermaster Corps to procure 150,000 sets of specialized jungle equipment for use in anticipation of ground operations in the difficult terrain of New Guinea. Twelve items were requested including a camouflage helmet liner with a band for attaching foliage, jungle uniform, jungle boots, cushion sole socks, floatation bladder, 18‐inch machete, machete sheath, jungle pack, waterproof clothing bag, jungle hammock, light‐weight jungle flashlight, and waterproof matchbox with compass. Together, these items were specially purposed to enable soldiers to travel light yet be self‐sufficient for up to ten days in a jungle environment where re‐supply was difficult.

Many of the new jungle items would be adapted from prototypes developed by an experimental jungle unit designated the Panama Mobile Force. This unit was organized in the summer of 1941 and was tasked with developing tactics and equipment specially adapted for jungle operations in defense of the Panama Canal Zone. Troops testing garments for jungle use favored the Army one‐piece herringbone twill work suit because it covered the entire body offering good protection against biting insects and cutting vegetation. The one‐piece HBT suit was modified for use in the jungle environment of Panama by dyeing it a dark green color or painting on a camouflage pattern. Captain Cresson H. Kearny, commander of the Panama Mobile Force, arrived in Washington, D.C. at the end of June 1942 with samples of his equipment for the purpose of further development and testing in conjunction with the Quartermaster Corps. It was shortly thereafter that Gen. MacArthur's request for jungle equipment was received. From this point onward development of jungle equipment was given the highest priority by the Quartermaster Corps and orders were given for the immediate standardization, procurement, and issue of the items MacArthur requested.

Army Ground Forces gave the official go‐ahead for the development of the jungle uniform on 28 July 1942. The concept of a darkened or paint daubed one-piece HBT suit advocated by the Panama Mobile Force served as the starting point for the new uniform. Though a light, mosquito-proof fabric was desired, development and procurement of such a material was not practical due to the urgency of the project. Thus, it was decided to use the 8.5‐ounce herringbone twill fabric already in supply. To provide camouflage, a multi‐colored dappled pattern would be printed onto the fabric using engraved rollers. The printed material allowed for a versatile, easy‐to‐use form of individual camouflage that could be mass‐produced and issued to troops when a specific situation required it. The use of a printed camouflage suit by the US contrasted significantly with the Japanese who mostly relied upon attaching natural foliage to the uniform or the use of Ghillie type suits and similar attachments for individual concealment. Dappled Camouflage Fabric

In the 1941‐42 period, the Army Engineer Corps developed several samples of camouflage material that were tested in conjunction with a variety of uniform designs. One concept undergoing testing around the time of MacArthur's request for jungle equipment was a standard two-piece herringbone twill uniform made up with a printed camouflage fabric having a dappled pattern. One version of this suit made use of a reversible fabric with green and brown dominant sides. A second version used the green dominant pattern paired with a solid green color on the opposite side. Ultimately, the reversible green to brown dappled pattern would be selected for use in the new one‐piece jungle suit. The green side of the fabric was considered the obverse and was to be used in lush jungle areas while the reverse was brown and was to be used in dry, sunbaked areas. The obverse was composed of two different shades of brown blotches and two different shades of green blotches superimposed on a light‐green background. The reverse was composed of three different shades of brown blotches superimposed on a tan background. Before the camouflage fabric could be manufactured and turned into jungle suits, the final colors and patterns for the design had to be selected so dyestuffs could be fashioned and the printing rollers cut. This process required coordination between the Engineer and Quartermaster Corps causing some delay in the project. Once this fabric was finalized it would be used by both the Army and Marine Corps in the manufacture of camouflage uniforms for the remainder of the war.

Army One‐Piece Jungle SuitWork on the jungle suit was completed in less than a month after MacArthur's request. The Philadelphia Quartermaster Depot drafted specification PQD 246 on 18 August 1942 for the new outfit designated Suit, Jungle, One-piece. On 31 August 1942, the jungle suit was declared standard issue triggering the release of large‐scale contract orders beginning in mid‐September. In its essence, the jungle suit held true to the main concepts of the Panama experiments in that it emphasized protection from the elements, camouflage, and sustaining the individual in the field. It should be noted that although the jungle suit was based on the one‐piece mechanic's suit, the two garments differed considerably in pattern and details. Several novel features were built into the new camouflage uniform that made it particularly suitable for jungle operations. A zipper front was used that allowed the suit to be quickly opened to allow the body to be cooled or kept closed when protection from the elements was desired. When closed, the zip‐up front and wrist adjustment straps provided excellent protection against jungle creatures and cutting vegetation. The leg openings were to be tucked inside special jungle boots or the standard leggings. Four large, expandable cargo pockets were provided that could hold enough ammunition, rations, or other critical items to sustain the soldier in the field for an extended period of time without the need for a field pack. Pockets were located only on the green side of the suit with two located on the chest and one located on each hip. Pressure snaps took the place of standard tack buttons on the pocket flaps to prevent snagging on foliage and equipment. The load carried in the pockets was supported by a set of suspenders attached to the inside (brown side) of the suit. To encourage cooling and drying and prevent skin irritation, the garment was cut in a generously bloused pattern, especially in the seat and crotch, so that it could hang away from the body. The suspenders also allowed the height of the crotch to be adjusted to the appropriate needs of the individual.

Marine Corps Two‐Piece Camouflage Uniform

|

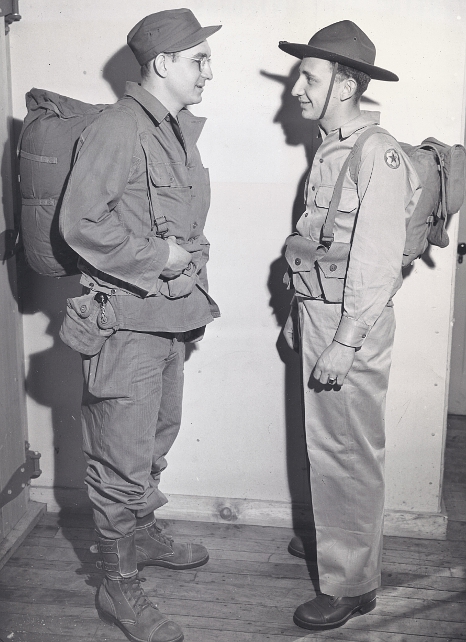

ABOVE: (Click or tap each article of clothing in above photo to see additional images) These two Marines wear printed camouflage uniforms during amphibious training in Hawaii in 1944. The Marine on the left wears the US Army one‐piece jungle suit with USMC camouflage helmet cover. The Marine on the right wears the USMC 1942 pattern two‐piece camouflage utility uniform with helmet cover. Note the USMC stencil above his left chest pocket. He has rolled up his sleeves and cut off his trousers at the ankles to counter the fact his suit was issued over‐sized.

Since early 1942 the Army and Marine Corps had both been experimenting with a variety of different camouflage patterns and uniform styles. Eventually, the US Army Engineer Corps came to favor a reversible, two‐piece design based on the standard HBT fatigue uniform that featured pockets on both sides ‐ a truly reversible uniform. There were at least two variations of this uniform produced; one having a camouflage pattern on one side and a solid color on the other and a second type that used a reversible green to brown fabric very much like the fabric that would eventually be adopted during WWII. Helmet covers were also fabricated to be worn with these suits and variations were made to fit over both the M‐1917A1 and M‐1 type helmets. These suits were made in quantity (to the extent that a number of them have managed to survive to this day) and were tested by the different branches within the Army as well as the Navy and Marine Corps. A photo of one of these Engineer suits, or one very similar to it, can be seen in Alec S. Tulkoff's book Grunt Gear undergoing testing by the Marine Corps.1 The Army Engineer suit more than likely played a role in influencing the Marine Corps' decision to adopt the two‐piece suit and helmet cover in the fall of 1942. After MacArthur's request for a jungle uniform was received, the Army chose to follow the work of the Panama Mobile force, abandon the two-piece suit, and instead concentrate on developing a one‐piece outfit. The working relationship between the Army and Marines during the developmental stage of the jungle suits appears manifest when the similarities between the experimental Army two‐piece suit with helmet cover and the final design adopted by the Marine Corps for use in the Pacific are considered.

Economics also more than likely played a role in the Marine Corps' decision to pattern the jungle suit after their standard utility outfit. Doing so would allow the Marine Corps to get the jungle uniform into production as quickly as possible using an already established pattern while utilizing the manufacturing capacity at their Philadelphia depot. This eliminated the need find external contractors and having them retool for a new uniform. The Marine Corps classified camouflage uniforms as specialized clothing, whereas the Army envisioned the jungle suit as a standard issue item available to all combat troops operating in a jungle environment. The development Army's fairly complex one‐piece jungle suit was an oddity at a time when many uniforms were undergoing simplification programs, including the standard Army one and two-piece HBT designs, in order to meet war‐time production demands. Even so, the Marines ended up acquiring substantial quantities of the Army one-piece jungle suit to supplement its supply of camouflage uniforms in the field. This was a common occurrence throughout the war years that the Marine Corps would fill field uniform supply shortages with Army and Navy types. Despite ending up with very different camouflage uniforms, the Army and Marine Corps tested similar designs during the developmental phase and ultimately the final designs shared the same fabric as well as the novel use of pressure snaps. After incorporating improvements derived from lessons learned on the battlefields of the South Pacific, the second‐generation Army and Marine camouflage uniforms that appeared in mid‐1943 shared much more in common than their predecessors. Jungle Uniforms DebutSamples of the Army's newly developed jungle uniform and equipment were rushed to the headquarters of US forces in Australia for evaluation in August 1942. Shortly thereafter initial orders of the jungle suit were authorized and would eventually exceed the 150,000 units originally requested by MacArthur. In mid‐September 1942, large‐scale procurement of the jungle suit commenced. Contracts were generally issued to manufacturers already experienced in making the Army's regular one‐piece work suit. From the summer of 1942 through the end of the year, contractors in the work‐wear segment of the garment industry focused on tooling up and producing the jungle suit while production of the regular one‐piece work suit was temporarily suspended to work on simplifying its design. By the New Year, the jungle uniform began to arrive in the Pacific en masse. It was issued to troops fighting in New Guinea in the Buna Campaign in January and February 1943. Meanwhile, specifications for the Marine Corps two‐piece jungle suit were likely completed sometime in September 1942. in fact, the helmet cover specifications show an adoption date of 17 September 1942. There is evidence to suggest that the jacket and trousers were adopted around the same time as the helmet cover. Author and researcher Alec S. Tulkoff indicates in his book, Grunt Gear, that the first contract for the Marine Corps jungle suit was issued in October 1942 with the first deliveries arriving at Marine units stationed on the West Coast in late December 1942 and early 1943. This timeline was established by examining war supply contracts for fabric and uniforms, Marine Corps memos, and archived photos.2 Photographs show Marines wearing camouflage in action for the first time while taking part in the New Georgia Campaign (20 June 1943 to 7 October 1943) where they were equipped with their new two‐piece uniforms and helmet covers. Period photos also show Marines making extensive use of camouflage uniforms and helmet covers during the Bougainville and Gilbert Island campaigns, especially on Tarawa Atoll. Shortcomings & ImprovementsOnce the new camouflage uniforms made it into combat operations, it didn't take long for deficiencies to become apparent. As much as troops preferred the one‐piece design in the jungles of Panama for its ability to provide protection against biting insects and thorns, conversely troops in the South Pacific generally disliked it because it was found to be too hot and heavy for the climatic conditions found there. Additionally, it was disliked because it required partial disrobing for toileting ‐ a fact that some felt negated one of its primary purposes since it left users exposed to insect bites during this process. These deficiencies caused many troops to cut the uniform in two with the purpose of creating a two‐piece uniform out of it. Dissatisfaction with the Army suit was immediate and prompted a quick dispatch of Quartermaster observers into the field for a first‐hand evaluation. The Marine Corps uniform, although not greeted with the same level of immediate criticism as its Army counterpart, had its weak points too. Its small, non‐expandable pockets lacked the necessary carrying capacity needed for an effective combat garment. Adequate for a simple chore uniform, the pockets were practically useless for carrying any appreciable amount of ordnance or other supplies crucial in a jungle combat situation where the ability to fight out of one's uniform was considered highly desirable. Since being adopted for the combat role, the Army had greatly increased the pocket capacity of its standard herringbone twill uniforms, while the Marine Corps, curiously, had not. The carrying capacity of the Marines uniform was further hampered by including only one lower coat pocket and one front and rear trouser pocket per side of the uniform in an effort to facilitate the reversible design. Another bothersome problem that cropped up was the tendency of the snap fasteners to pull through the fabric after repeated use. Once damaged this type of fastener was difficult to repair in the field. After observing firsthand the shortcomings of the one‐piece jungle suit and its rejection by troops, Quartermaster field observers recommended the immediate adoption of a two‐piece uniform made of a lighter fabric. Dissatisfaction with the one‐piece suit was of such intensity that it was quickly withdrawn from combat use and issued to service and supply troops instead. Quick action was taken to develop an improved camouflage uniform and by the spring of 1943 work on a new two‐piece outfit had been successfully completed. On 4 May 1943, the one‐piece jungle suit was declared limited standard. This meant the suit would continue to be issued until exahusted, but no new orders would be placed. Though a major complaint about the one‐piece suit was that it was too hot and heavy for jungle use, a satisfactory substitute for the HBT fabric could not be found. Thus, the same 8.5‐ounce HBT fabric was carried over to the new outfit. The new two‐piece camouflage uniform retained large cargo pockets on the chest and outer thighs, introduced concealed fly buttons throughout, included gas protection features, and the trousers were outfitted with suspender buttons around the waist. Interestingly, the suit was simply referred to as a camouflage uniform and the word jungle was not used in the official nomenclature. Also, even though the jacket and trousers were special garments equipped with gas protective features, the word special was not used in the nomenclature to denote this as was common practice with other items. The Marines also worked quickly to improve their camouflage uniform and by the fall of 1943 were issuing a new two‐piece outfit designed specifically for combat operations. Both the Coat, Combat, Camouflage and Trousers, Combat, Camouflage, as they were officially named, had extra‐large cargo compartments built into them similar to the type used in bird hunting apparel. The coat had one of these pockets on each side of the chest and the trousers one large pocket extending across the seat. The added carrying capacity of the new uniform eliminated the need to haul a cumbersome pack during amphibious assaults by allowing Marines to carry most of their basic equipment in the uniform, such as rations, a poncho, ammunition, floatation bladders, etc. In addition, the new Marine Corps uniform returned to tack buttons for the main openings of the coat and trousers, added gas protection features, and the trousers were designed so that they could be used with suspenders. By mid‐1943 the Army and Marine Corps camouflage uniforms had evolved to become more alike and embody a fundamental set of similar desirable characteristics consisting of a two‐piece design, ample cargo pockets, trousers which could be supported with suspenders, and the inclusion of gas protective features. Cancellation & Reclassification

As the second‐generation uniforms were being introduced, a more fundamental question arose regarding the effectiveness of the camouflage pattern itself. Field reports indicated that when the camouflage uniform was worn against a dark jungle background men became more visible ‐ an effect that became even more pronounced when men were in motion. This was primarily due to the very light background used for the fabric over which the dappled pattern was printed. Though camouflage uniforms were found to be acceptable for men in static positions, by this time most combat units were involved in offensive operations requiring continual movement through the jungle. Furthermore, testing had revealed that a single shade of dark gray‐green offered the most effective concealment for a combat uniform that was to be worn against a variety of backgrounds. As a result, the General Staff, Army Ground Forces, declared the camouflage pattern material unsuitable for jungle operations. It was determined that the standard issue HBT uniform, converted to the dark green olive‐drab Shade 7 in March 1943, would be preferable for use in jungle environments. Thus, in January 1944 the Army General Staff directed that the camouflage uniform be declared limited standard as soon as all of the camouflage material on hand was expended. During March 1944, the last of the contracts for the Army two‐piece suits had been fulfilled and on 30 March 1944, the General Staff approved a Quartermaster Corps Technical Committee recommendation that shipments of camouflage uniforms into theaters of operations be halted. It is interesting to note that on page 16 of the February 1944 Army Manual, Camouflage of Individuals and Infantry Weapons, a warning is issued against wearing the jungle suit in extremely dark sections of the jungle.

The same fault that the Army pointed out in the camouflage pattern caused the Marine Corps to take concurrent action in restricting the use of their camouflage uniforms. It is worth pointing out that in the Army Quartermaster Historical Study No. 16, Clothing the Soldier of World War II, in the section discussing jungle clothing, it states that USMC officers agreed with the Army's conclusion that the camouflage fabric, based on visibility issues, was unsuitable for jungle operations.3 The book Grunt Gear refers to the existence of an ambitious Marine Corps objective that was in place in late 1943 that sought to procure enough camouflage uniforms so that one suit would be available for each man assigned to a combat unit within the First Marine Amphibious Corps. Though it is noted that this procurement objective was only intended to be temporary, it does demonstrate the strength of the commitment the Marine Corps had to their camouflage uniform program at that time. However, without coincidence or surprise, the Marine Corps ended this procurement program concurrent with the Army ending overseas use of the camouflage uniform. This was accomplished by an April 1944 memo issued by the Commanding General of the Fifth Amphibious Corps in which new directives greatly reduced the number of camouflage suits that would be made available to Marine units going forward. It also identified the standard Marine HBT utility uniform as the primary uniform that would be issued for use in the Pacific Theater of Operations.4 In retrospect, the decision by the military to effectively end the camouflage uniform program in early 1944 seems rather sudden and curious considering it came so shortly after considerable effort was expended producing the much improved second‐generation uniforms. Though overseas shipments of camouflage uniforms were halted in March 1944, those already in the supply lines continued to be issued, especially to service and supply troops. Photos from the campaigns that followed the spring of 1944 seem to confirm the withdrawal of camouflage uniforms from frontline service. This is especially the case with the second pattern uniforms where any photos of them being used overseas are extremely difficult to come by. Despite the gradual disappearance from frontline areas, camouflage uniforms continued to be issued stateside in lieu of standard HBT uniforms for field training sessions and amphibious landing exercises. There is some very limited photo evidence of the second‐generation Marine uniform being used in the Marianas (Saipan) and Volcano (Iwo Jima) Island Campaigns. Probably the most recognizable photos of the Army two‐piece suit came not from the Pacific, as one would expect, but from the Normandy Campaign where it saw limited use in frontline service. However, it should be remembered that the Army's decision to halt the issue of camouflage uniforms in theater of operations occurred more than a month before the D‐Day landings of 6 June 1944, thus any substantial use of these uniforms would have been short‐lived.

The camouflage pattern by no means died out during WWII. It was adapted to many other items during the War including packs, ponchos, shelter halves, parachute canopies, and other small items ‐ some official issue and some field made. Additionally, it is important to note that the USMC helmet cover was never withdrawn from service during WWII. In fact, the helmet cover was the longest lived camouflage item to emerge from the WWII period and remained a standard issue item into the early 1960s until it was eventually supplanted by the new "Wine Leaf/Mitchell" pattern adopted in 1959. The helmet cover survived as long as it did because, in addition to camouflage, it offered other important benefits including the elimination of sun glare from the helmet and the reduction of metallic ring when the helmet was struck. Interestingly, the second pattern USMC camouflage suit made a limited but noticeable revival during the Korean War. Period photos from the Korean Theatre seem to suggest that the second pattern USMC suit saw more use in the field there than at any time during WWII.

LegacyThe camouflage uniforms developed by the US during WWII left a legacy that extended into the post‐war era and beyond. Failure of the camouflage uniform to fulfill its promise, along with many other garments developed early in the War, induced the Army to implement a more rigorous testing program. Beginning in 1943 new items would be subjected to an extended period of field testing that included limited scale issues in a theater of operations to work out all possible deficiencies before authorization for widespread adoption was granted. An example of this new methodology was implemented during the gradual introduction of what is now commonly known as the M‐1943 field clothing. In the 1960s, US military involvement in Vietnam once again compelled the use of camouflage uniforms due to operations being conducted in a landscape that included areas of dense foliage and jungle terrain. While camouflage helmet covers were in use at this time, including the WWII type discussed above, there was no standard‐issue camouflage uniform being produced by the US military. To compensate for the lack of a camouflage uniform, some individuals purchased commercially made hunting garments that used the old WWII camouflage pattern to wear in Southeast Asia. During the 50s and 60s use of the WWII camouflage pattern was carried over to the outdoor garment industry where it was used mainly in hunting garments. In the commercial market, the design was colloquially referred to as the "duck hunter" or "frog-skin" pattern. Additionally, uniforms with camouflage patterns very similar to the type the US used in WWII were produced by regional manufacturers in places such as Korea and Japan and were sold to US military advisors and other troops for wear in Vietnam. When WWII ended there were large surpluses of camouflage uniforms left in military stockpiles. Quantities of these uniforms were sold off by the Government into the surplus market after the war where some were marketed in outdoor and mil-sup catalogs as hunting garments. Others found their way into the militaria market, or into Hollywood costume wardrobes. Many WWII era camouflage uniforms can be found today in unissued condition, especially the second pattern uniforms. This is a result of the jungle uniforms program being effectively cancelled in March 1944 just after large orders of second pattern uniforms had been procured. This situation left many uniforms never to be issued and sitting in military supply depots to be disposed of in later years. Fortunately, in recent years there has been a great deal of interest in collecting and preserving US camouflage uniforms from the WWII era. Interest in these uniforms is strengthening for several reasons. The garments themselves are rightfully being recognized for their place in the annals of US military uniform history. The fact that they were the first printed camouflage uniforms to be issued in any meaningful amount is significant in itself. Furthermore, these uniforms have become strongly associated with the US Marines and the early pivotal battles fought against the Japanese on the South Pacific islands of New Guinea, New Georgia, and Bougainville. To add to this, in November 1943, some of the most dramatic images of combat captured during WWII were filmed in the Central Pacific as US Marines assaulted Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll in the Gilbert Island chain. This footage was presented in a color feature entitled With The Marines At Tarawa and contains indelible images of Marines, many wearing camouflage uniforms and helmet covers, during their violent struggle to capture the Island. Iconic images such as the Tarawa assault, the Iwo Jima flag raising, and others have helped to create a strong visual connection between the camouflage pattern and the Marines of WWII. Perhaps it could be said that the camouflage pattern of WWII is inextricably linked to the US Marine Corps and the bloody battles of the Pacific War.

1 Tulkoff, Alec S., Grunt Gear. 2nd Printing, 2006. (San Jose, CA: R. James Bender Publishing, 2003), 38.

|